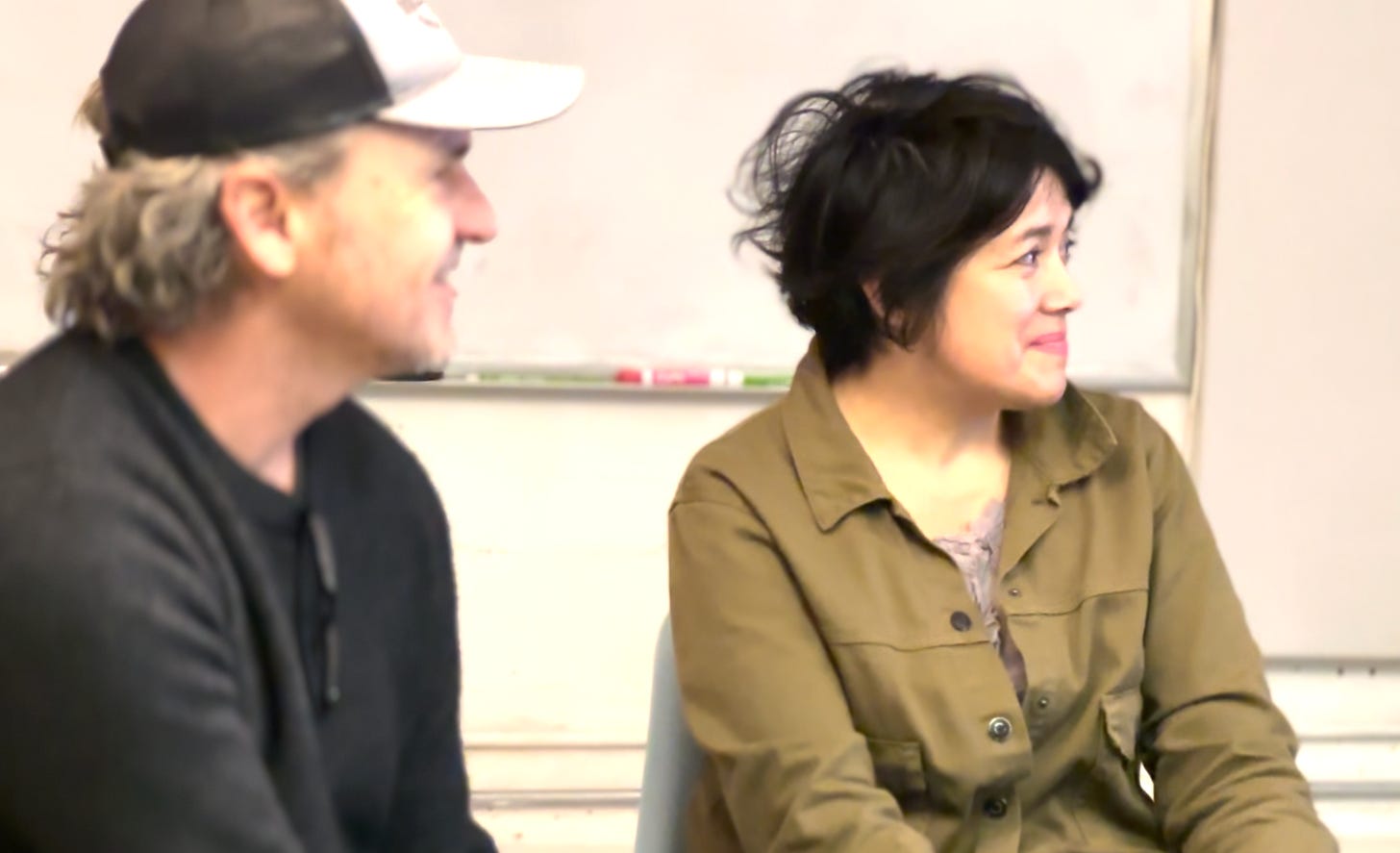

When I was given the chance to host the live on stage conversation with Werner Herzog for City Arts and Lectures in San Francisco I was barely able to believe it. What a gift! What a chance!

In preparation I did all the reading–and watching. I watched Aguirre Wrath of God again, marveled at Grizzly Man and the tragedy–or maybe triumph?–of Timothy Treadwell. I watched Stroszek again, my favorite Herzog movie. I watched a lot of his documentaries. Herzog is preposterously prolific, having made over 70 films, so if you can spend weeks in the dark, watching. (soon you can, at the PFA Herzog retrospective in November). They are all great; as Roger Ebert said, not a single one is compromised, even the failures are magnificent. I watched the video of him getting shot while being interviewed for the BBC, possibly the most Herzog response ever: he looks mildly startled and looks up. “What was that?” he says, once again cheating death. He’s a pop icon and has played various villains in movies and TV, including in Jack Reacher. He’s been in The Mandalorian and The Simpsons, and my favorite of his roles: the downcast voice of a heartbroken plastic bag, who’d lost his “creator”, the woman who first brought him home from the grocery store.

Herzog has also written books and poetry. He’s said that he thinks he will be remembered more for his writing than his films. Films are the voyage, he says. But writing is home. He’s just written a memoir, Every Man for Himself, and God Against All, which is what we would be talking about, in San Francisco, soon. His publicist said: don’t ask about his films. Talk about his memoir, his books and his writing. OK.

The memoir was everything I’d hoped: ecstatic truth, the wisdom of the snake; the exhilaration of getting shot at and missed, episodes of arrest and detention, rule-bending and working around the obstacles endlessly presented by bureaucrats and uniformed underpersons. Mike Tyson appeared unexpectedly. A Caliban on the island. There was a paean to the Oxford English Dictionary, the actual, physical, 20 volume set, which he thinks of as one of the greatest cultural achievements of all time. I agree! There’s more charm and sweetness than you’d expect from this sometimes gruff Bavarian man of the mountains, the tundra, the jungle, the desert.

After spending much of a day with him, I left feeling energized and ready to undertake ambitious projects! I thought–knew!–what I was capable of. This is what it can be like being around people like him. I hope some of you got to hear the conversation in person, because in person is different than watching it on a screen. Herzog was insightful, warm and funny; he told stories uplifting and harrowing and often completely unexpected and at the end he got a standing ovation, which went on and on. It made him happy. And made me happy.

Now, a week later, I am thinking about that experience, and how people like Herzog make good and hard work possible for others. If what’s impossible for others is possible for him, it’s possible for you too. You can ask yourself, when you find someone worth emulating, what would they do? You could make a bracelet, and whenever you were about to give up, when things got too hard you could snap it against your wrist and remember who you meant to become, get your gumption going again. What Would Herzog Do?

We know more about how Herzog creates his movies because he talks about it a lot, first of all, because he is asked about it, because the way he works is fascinating and sometimes extreme. There’s a lot of second hand material, accounts of the making of his work too. Les Blank made The Burden of Dreams, a documentary of the making of Fitzcarraldo, a movie about the nearly impossible and completely irrational desire of a man to move a steamboat over a mountain, to build an opera house, so Caruso could sing there, in the middle of the jungle. The making of the Fitzcarraldo was itself even more difficult than moving the steamboat, more difficult than the story it was meant to depict. It was like a reflection, phylogeny recapitulates ontogeny, Triple E Extreme Exaggerated Ekphrasis, a Portrait in a Convex Mirror (Ashbery’s), a movie bursting from the borders of itself.

What Would Herzog Do? Maybe walk over mountains, machete his way through a jungle, travel to remote, icy, volcanic, idyllic or dangerous regions, consort with grizzly bears, be a ski jumper. He would definitely advise you to love deeply. Definitely advise you to read. When Herzog advertised his Rogue Film School in 2014 (which was already full by the time I applied, to my great disappointment) he published a reading list, which included The Peregrine by J.A. Baker, which he frequently recommends (it’s great, read it) The Poetic Eddas and The Conquest of New Spain, neither of which I finished.

What Else Would Herzog Do? For one thing, he probably wouldn’t bother reading anyone else’s reading list, but stick with what interests him. He’d stick to his own vision. He doesn’t see very many movies, maybe 3 or 4 a year. Unlike Scorcese, who sees movies constantly. Herzog has conviction in his own filmic vision and he’s not influenceable. At dinner before our talk someone asked if he’d seen the Barbie movie, maybe just to bait him? Unsurprisingly he hadn’t seen it, but he had seen the ads. He assumed a sour expression. “Hell,” he concluded. “The world of Barbie looks like how I imagine hell.”

It’s a privilege to be around brilliant people doing brilliant things, and gives you the energy you need to work on your own great undertaking, your own impossible project. So make the effort to go out and see amazing people like Herzog at places like City Arts and Lectures, 92nd Street Y, or other places near you. Read. Don’t get distracted by meaningless tripe. Don’t fight for prizes not worth winning. Follow through, get it done, persist, learn to pick locks and walk long distances. Be strong, be smart, bring your toothbrush, be kind, work hard, be loving, be you, be beautiful.

Bring your toothbrush? It’ll make sense when you listen to the conversation.

More things to read, see and do:

- My conversation with Herzog will come out on December 3, 2023 on KQED. Watch for it!

- Listen to the Ingenious Podcast.