Listen to the show on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you listen.

In his first book, Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, Dave Eggers wrote about snakes shedding their skins.

“We feel that to reveal embarrassing or private things, like, say masturbatory habits (for me, about once a day, usually in the shower), we have given someone something, that, like a primitive person fearing that a photographer will steal his soul, we identify our secrets, our pasts and their blotches, with our identity, that revealing our habits or losses or deeds somehow makes one less of oneself. But it’s just the opposite, more is more is more – more bleeding, more giving. These things, details, stories, whatever, are like the skin shed by snakes, who leave theirs for anyone to see. What does he care where it is, who sees it, this snake, and his skin? He leaves it where he molts. Hours, days, or months later, we come across a snake’s long-shed skin and we know something of the snake, we know that it’s of this approximate girth and that approximate length, but we know very little else. Do we know where the snake is now? What the snake is thinking now? No. By now the snake could be wearing fur; the snake could be selling pencils in Hanoi. The skin is no longer his, he wore it because it grew from him, but then it dried and slipped off and he and everyone could look at it.

And you’re the snake?

Sure. I’m the snake. So, should the snake bring it with him, this skin, should he tuck it under his arm? Should he?No?

NO, of course not! He’s got no fucking arms! How the fuck would a snake carry a skin? Please.― Dave Eggers, A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius

We’re the snake.

I deeply believed at one time that we were all the snake and that by being the snake (at least how Dave is describing it here, back in his very first book) the more we showed of ourselves and left our skins behind, the better. Of course that doesn’t mean we should all go online and tell on ourselves. But we should be able to do what writers do (or artists, musicians—anyone really—priests, dog trainers, maintenance workers, phlebotomists) which is make something which, and be somebody who, reveals ourselves and is true to our warty, actual selves. Not be too precious about ourselves. We sound so young when we say this, but: Let’s stay true to the people we were and the dreams we had.

The story about how indigenous people didn’t want to be photographed because they feared it would steal their souls has new currency in the age of AI. I know this first hand. I was a big advocate for free culture and the open software movement in the early aughts, implementing Creative Commons licenses in Flickr, thereby creating the largest library of shareable media in the world, at least, at the time. I shared my own photos with Creative Commons licenses and joined the Creative Commons board. Artists and filmmakers and other creative people were able to use them to make fantastic things. Jonathan Coulton wrote a song (and made a short movie) named after Flickr using the Creative Commons licensed photos—that’s MY dog with glasses!

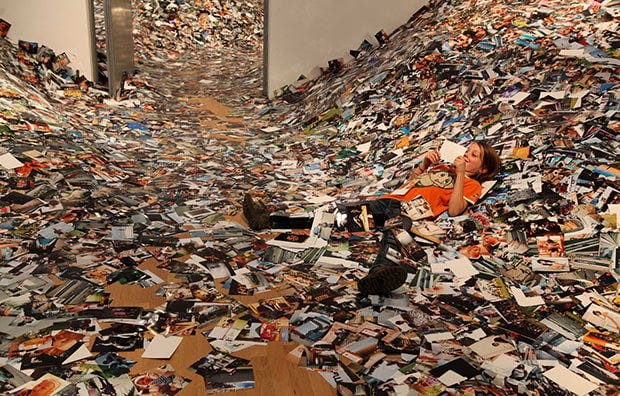

Flickr photos appeared in low budget movies, in band posters, in this incredible installation by Erik Kessel at a gallery in Amsterdam. The installation featured prints of every single photograph uploaded to Flickr within a 24-hour period. The more than a million photos are piled up nearly to the ceiling, and spill over into several rooms.

I never got to see it in person. It was an artwork about how we are drowning in photos, in media. How no one can look at all of the photos. It was still a newish idea at the time, 2011. What a wonderful time that was.

It was an era of optimism and trust. We trusted humanity. We knew people to be honest, well-meaning. We trusted technology, audiences, artists—there was so much trust, we were just bursting with trust. It seems almost inconceivable now, so jaded and weary we’ve become. We believed that people are essentially good, operating in good faith, trustworthy, reasonable. We were not wrong. But we discovered that even if 999 out of a thousand people are honest and trustworthy, one bad actor can be incredibly destructive. A mob of angry tweeters. Or, enemy nations.

I talked about this with Chris Anderson, who had been the Editor-in-Chief of Wired magazine, on my last podcast Should This Exist?. He had an open source drone company, 3D Robotics, and they open sourced their drone software. A lot of hobbyists hacked their Lego Mindstorms and had a lot of fun making flowers or M&Ms rain down on children’s parties, searching for lost elephants in vast African wildernesses and other great things. Then one unhappy day, on the front page of the New York Times, Chris learned that ISIS had been using his drone software to kill people.

This was about as bad of a consequence as you can imagine. The worst consequence of sharing something online. But it was also happening in my world, the online world. Media, social media, was becoming more and more toxic. We had started out as the aforementioned snakes, sharing our photos, jokes, stories, poems, lives. But at many of the hosting companies, it was no longer about sharing; a lot of it was about stealing. Harvesting and exploiting your “data”, which you had thought of as your life. To my surprise, chagrin and increasing anger, I realized that the Creative Commons licensed photos on Flickr were being used to train AI. That even though no human could ever look at every single one of the photos in Erik Kessel’s artwork, or in the Creative Commons archive, or anywhere on the internet, a computer could.

Another conversation I had during the first season of Should This Exist? was with Sam Altman of OpenAI, a company we now know best as the maker of ChatGPT, but which at the time was a non-profit looking to protect humanity from the consequences of what was in the process of being invented. Money came, moral compasses spun around and lost true north—we know the rest. And now we’re seeing the results, watching the whole experiment unfold in real time: people’s faces and data and art and words being stolen, repurposed and put into formats and contexts they never intended or wanted, exploited for purposes that hadn’t existed when they innocently shared pictures of their weddings and kittens online, swindled and diddled and flimflammed and worse. All those words and images, pressed into service for manufacturing lies, flipping elections, and creating enemies where once were friends.

Which brings us to today’s podcast with Dave Eggers. He is the writer, artist, philanthropist and co-founder of 826 Valencia, a non-profit tutoring center for kids that teaches the next generation reading, writing and how to tell their own story. Which seems a paltry effort when you look at the giants and masters of the tech universe thrusting their rockets into space and colonizing everyone’s brains. Just patiently teaching a kid to read and write. Dave, who stands for a value system that is contrary to all this.

Dave and I go way back. We worked together circa 1996-8, at Salon.com, one of the very first online media publishers, which published, and still publishes, thinky articles on society and culture. They also host thoughtful online conversations and civil discourse. Again, it was an amazing time to be online.

Now I’m on the board of McSweeneys, the publishing company that Dave also founded. It publishes books and magazines, old media. So Dave and I have invested a lot of our energy into making places and spaces for writers doing creative work, finding an audience and getting paid. But these are fraught times for writers. The writers in Hollywood are on strike, AI is taking their jobs, teachers are saying the high school essay is dead. You’re here too and you’ve seen it—there’s a lot of dread to go around. Think we’re reactionary luddites? I don’t think so. Techno-optimists turned tech skeptics, maybe. I think we’ve all become a lot more wary since our salad days.

In any case, there’s a lot of these values and thinking and ideation in this podcast. It is a special episode because Dave and I are old friends, and share a lot of the same hopes for the humans. So give it a listen!

I’m so proud of this podcast, Ingenious, which was the co-creation of me and my friend and producer Mary Beth Kirchner, with the tireless assistance of Jyri Engestrom and Beth Malin and the Yes VC team and a host of others. Including the brilliant guests who have always found a way to surprise me, energize me and pave new avenues of thought. I hope it’ll do the same for you.

Thanks Dave, for this and all you do. How far that little candle throws his beams! So shines a good deed in a weary world.

Some resources:

- Listen to the podcast Ingenious with Dave Eggers on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you listen

- Follow me here or on my substack

- Contribute as a donor, volunteer, fan or student to 826 Valencia

- Subscribe to The Believer or the McSweeneys Quarterly

- Buy a copy of the beautiful wood-covered version of The Eyes and the Impossible

As I was reading about Andrea Roberts’ research into “freedom colonies”, the name bothered me. Freedom ––as I’d always understood it from elementary school, from the Pledge of Allegiance we recited every day, facing the flag and with our hands over our hearts, from Woody Guthrie songs and the Star-Spangled Banner–freedom should be general across the nation, from sea to shining sea, from the redwood forest, to the gulf stream waters, one nation, liberty and justice for all–and not confined to a colony. The word “colony” (per my trusty Barnhart) means “a settlement dependent on another country”–though further back it’s found to derive from cultivation, tilling, inhabiting.

As I was reading about Andrea Roberts’ research into “freedom colonies”, the name bothered me. Freedom ––as I’d always understood it from elementary school, from the Pledge of Allegiance we recited every day, facing the flag and with our hands over our hearts, from Woody Guthrie songs and the Star-Spangled Banner–freedom should be general across the nation, from sea to shining sea, from the redwood forest, to the gulf stream waters, one nation, liberty and justice for all–and not confined to a colony. The word “colony” (per my trusty Barnhart) means “a settlement dependent on another country”–though further back it’s found to derive from cultivation, tilling, inhabiting.